Canada is facing an exploding housing and homelessness crisis: unsheltered homelessness has doubled since 2018, average rent has increased 11% in the past year alone, and in Toronto, the monthly cost of an average one-bedroom apartment for rent increased at twice the national rate over the past year to a whopping $2,506 per month.

Toronto’s next mayor has a huge challenge before them – but also an opportunity to stop a housing catastrophe.

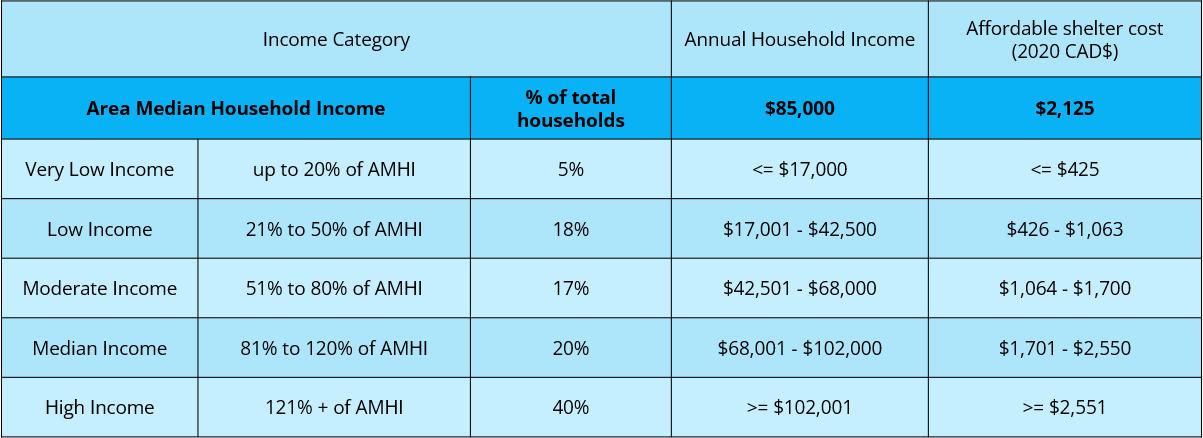

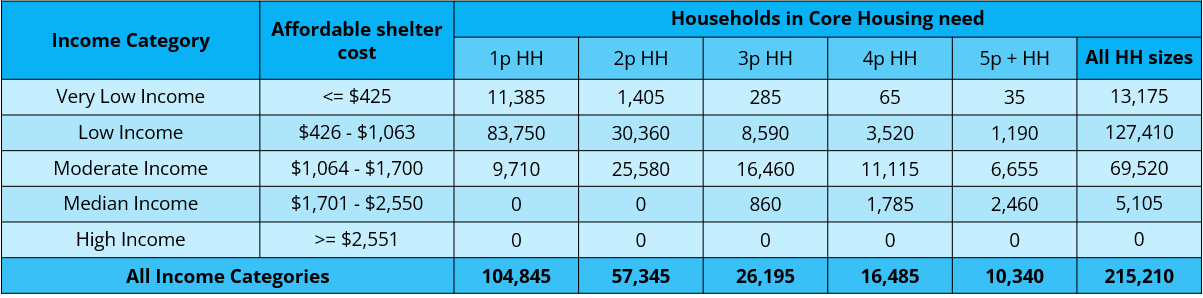

According to new housing data from the 2021 census, you need to be earning almost 120 per cent of Toronto’s median income to afford a one-bedroom apartment in the city. The data on core housing need in Toronto – meaning those living in unaffordable, poorly repaired and/or overcrowded housing – is dire: Very low income households can only afford $425 per month for housing. Meanwhile, the average market rent for a single room in Toronto is $1,024. Low-income households, who generally earn minimum wage, can afford at most $1,063 a month for their housing – that’s less than half the cost of an average one-bedroom apartment.

Even more worrying, this 2021 census data wildly underestimates core housing need in two ways.

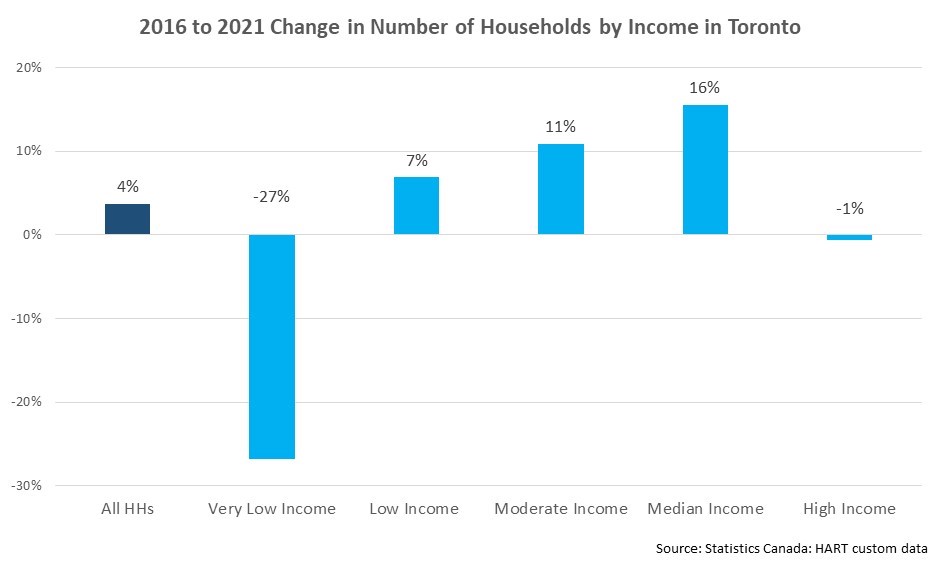

First, temporary COVID-era income supports such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) predominantly helped very low-income households afford their rent. According to our calculations, CERB was an effective natural experiment of the life-saving possibilities of a federal guaranteed annual income. But these income supports didn’t continue and greater homelessness resulted.

Second, the data also leaves out the needs of many people who don’t live in private accommodation, including 7,347 homeless people in the city, over 200,000 university and college students, thousands of people living in inadequate congregate housing, from rooming houses to long-term care homes, and others. Most of these households are very-low-income.

The City of Toronto has pledged to build 285,000 more homes by 2031, but this must be a floor, rather than a ceiling, and must comprise a majority of low-cost rentals. So how can Toronto scale up its affordable housing to stem the rising tide of homelessness? Many levers are federal, including doubling the stock of non-profit housing to 1980s levels. Others are provincial, like adequate income, health and social supports for a Housing First approach.

But Toronto also has three big levers it has not yet adequately used.

The first is to unlock well-located land for genuinely affordable homes: the municipality is moving forward with rezoning about two thirds of its residential area, including allowing licensed rooming houses across the city. However, the City needs to move from ‘allowing’ these options to actively encouraging them. It needs to co-design new rules with developers that enable rapid approvals – and then heavily tax those who sit on approved sites. It needs to move most affordable developments from risky and costly public hearings to delegated approvals by staff. Luxury zoning and building code requirements need to be eliminated.

The second lever is to unlock well-located government land for non-profit housing. Toronto’s Housing Now program includes 17 sites that were to be leased by private developers in return for 11,000 rental apartments for low-income tenants. Not one home has been constructed since 2019’s announcement. In contrast, Vancouver leased four sites to a non-profit in 2016, leading to over 350 mixed-income social and supportive homes completed by 2019, with 1,000 more slated for the end of 2023. Vancouver has even higher construction and labour costs, but a 2019 study found that using non-profit developers saves 32 per cent of costs. The dividend of favouring non-profit providers is clear.

The third lever is a more progressive property tax system. In the longer term, Toronto needs to rethink its reliance on development contributions to pay for infrastructure that benefits everyone. Homeownership is now locked out to all but the richest of Toronto households, yet Toronto property tax rates are amongst the lowest in Canada. Progressive property taxes, such as luxury home taxes, a higher Vacant Home Tax, and land value taxes that look at the underlying value of the land rather than what is built on top of it, have the potential to raise money to address homelessness and inadequate housing, as well as redistribute housing wealth in Toronto.

Housing is essential to the well-being of a person and to building sustainable and inclusive communities, a right recognized under federal law. This election we have a chance to address Toronto’s housing and homelessness emergency by voting in a mayor who will take strong action. We cannot wait for this emergency to become an even greater disaster.