Among the overlapping and compounding crises in Canada, housing continues to make headlines and impact millions of Canadians. Federal policymakers clamor to present the best policy to ease the cost of housing, debating the merits of carrots and sticks, and exactly how many new homes we need to improve affordability (hint: it’s a lot). There has been one key area of federal jurisdiction that has been underrepresented in these discussions: federally-owned land.

In many European and Asian countries (Singapore, Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands etc.), large scale non-market housing (municipal, cooperative, supportive) is enabled through assembly of large land parcels funded by national governments, grants and/or long-term low-interest loans, plus some demand-side housing allowances. These are successful examples because governments own a lot of land, and the purchasing land is one of the most significant costs of building housing, especially in major centres. New housing could reach new levels of affordability simply through an effective federal land-use policy; an effective framework is outlined in this article.

The existing Federal Lands Initiative (FLI) is a $200M fund that focuses on the transfer of surplus federal land for the purpose of building affordable houses. This is not a new concept; the federal government directly leased land and provided funding for provincial government to acquire land during two other recent phases:

- Victory Houses 1943-1960: federally purchased and municipally leased land, direct construction of homes, rent until 1949 and afterwards sale of homes

- National Housing Act amendments 1964 and 1973 – 1985: federal funds for provincial (after 1973 mainly municipal and other non-market) assembly of land, grants (after 1973, emphasis on long-term low-interest loans), plus some demand-side housing allowances

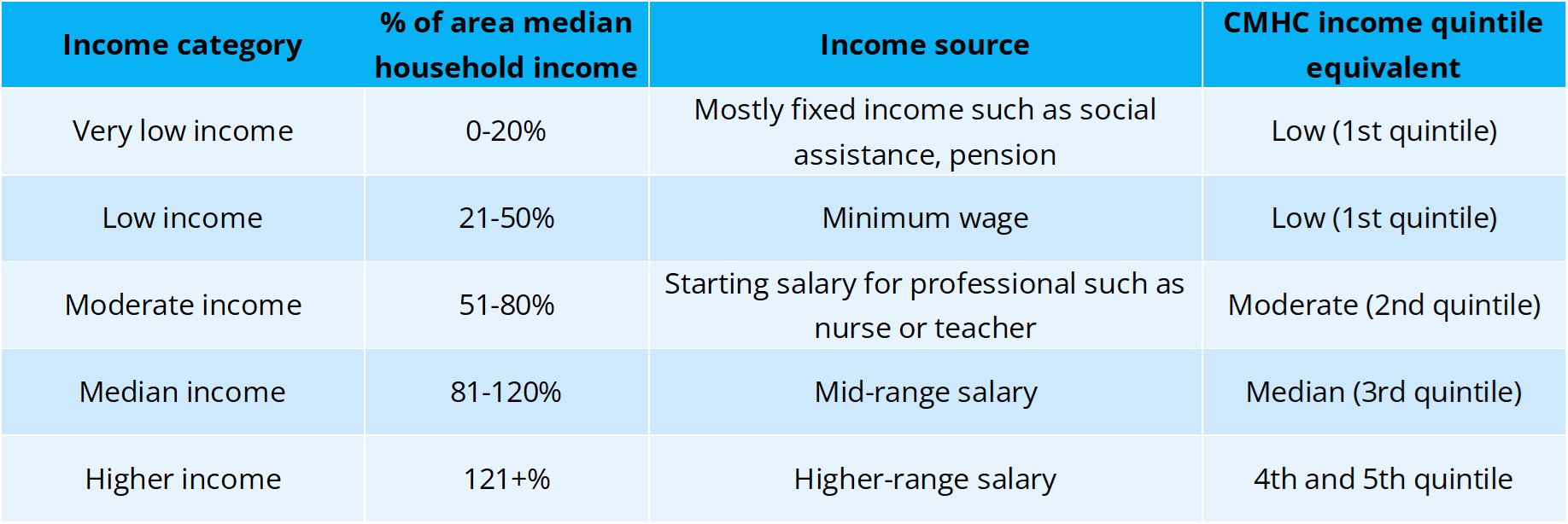

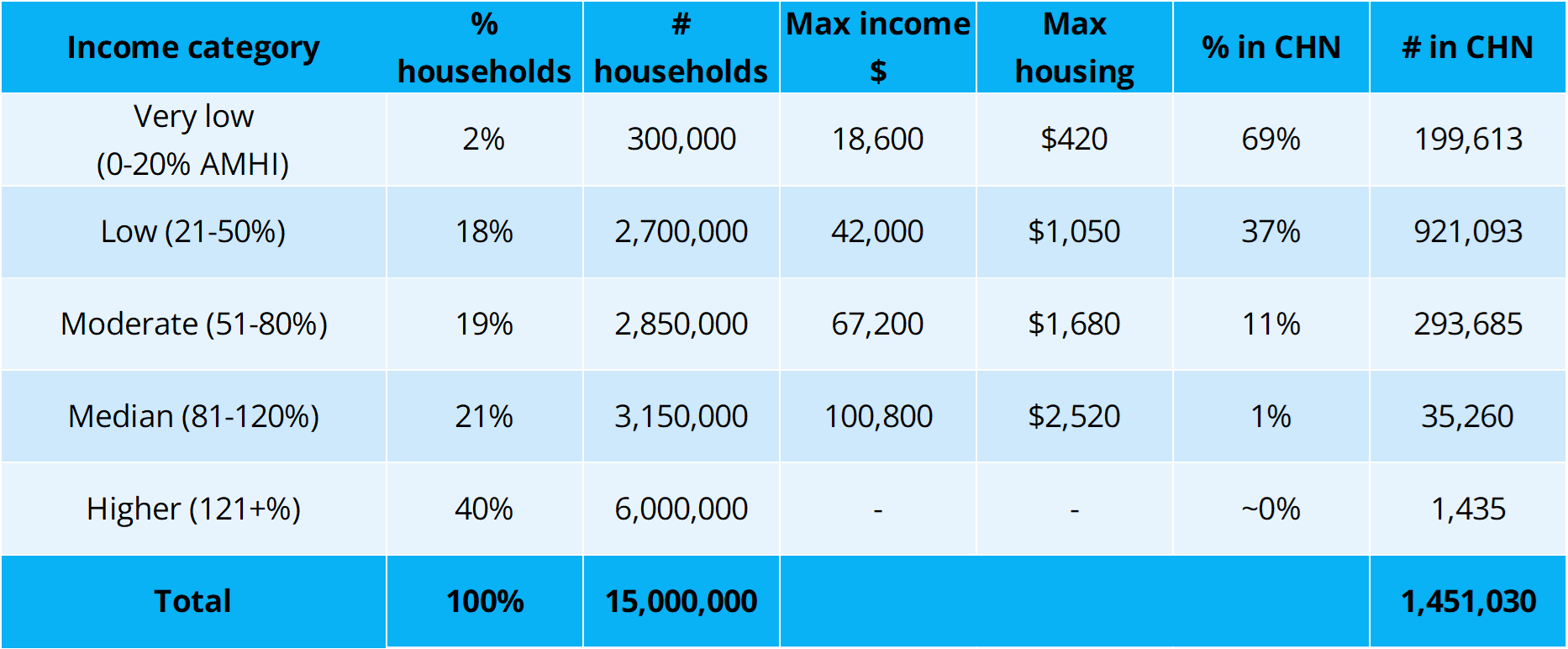

Based on Housing Need Assessment methodology developed by the Housing Assessment Resource Tools (HART) project and recommended by the Housing Accelerator Fund as a basis for municipal housing need assessments, we find that 14% of households in core housing need and 100% of individuals in chronic homelessness are very low-income. Nationally, they can afford a maximum of $420 per month in housing costs; there will be variations provincially and municipally, based on welfare rates and median local household incomes. A further 63% of households in core housing need are low-income and can afford a national average of $1,050 in monthly housing costs (Table 1 and 2).

Table 1. Definitions of affordability (HART, 2023)

Table 2. Numbers, proportions, and maximum affordable housing costs of each household income category in core housing need (CHN), 2021 Census (HART, 2023)

Governing principles for a new FLI

Given that this has been done before, and need has never been higher, we suggest a set of principles governing an improved Federal Lands Initiative:

- Non-market housing for greatest affordability: As a long history of Canadian and international literature points out, households in the lowest income quintile will not have their needs for affordable adequate housing met by the private market. Non-market housing may provide the biggest cost savings, as well as long-term affordability. But non-market housing requires both direct subsidy through grants, low-cost long-term financing, and housing allowances, and indirect subsidy through free leased land and waived fees and taxes (e.g. application fees, development contributions, land transfer tax, property tax, HST) to meet the needs of very low- and low-income households.

- Free leased land for greatest viability: After profit, the biggest cost savings can be realized through free land: between 8-23% of total cost, depending on the geographic context.

- Long leases for greatest payback: Sixty to 99 year leases maintain affordability covenants for the longest period.

- Scale matters: Larger land assemblies can be developed into housing more quickly and efficiently, especially when using an industrialized process such as prefabricated modular construction. Federal land sites adjacent or near to other government land sites (or vacant well-located land suitable for acquisition) should be prioritized. Scale requires sophisticated non-market developers, suggesting that a list of preferred providers with at least 1,000 homes (or a community land trust representing combined assets of at least 1,000 homes with strong development capacity) be created by the federal government. Partnership bids should be encouraged (e.g. municipal public housing developer with supportive housing provider).

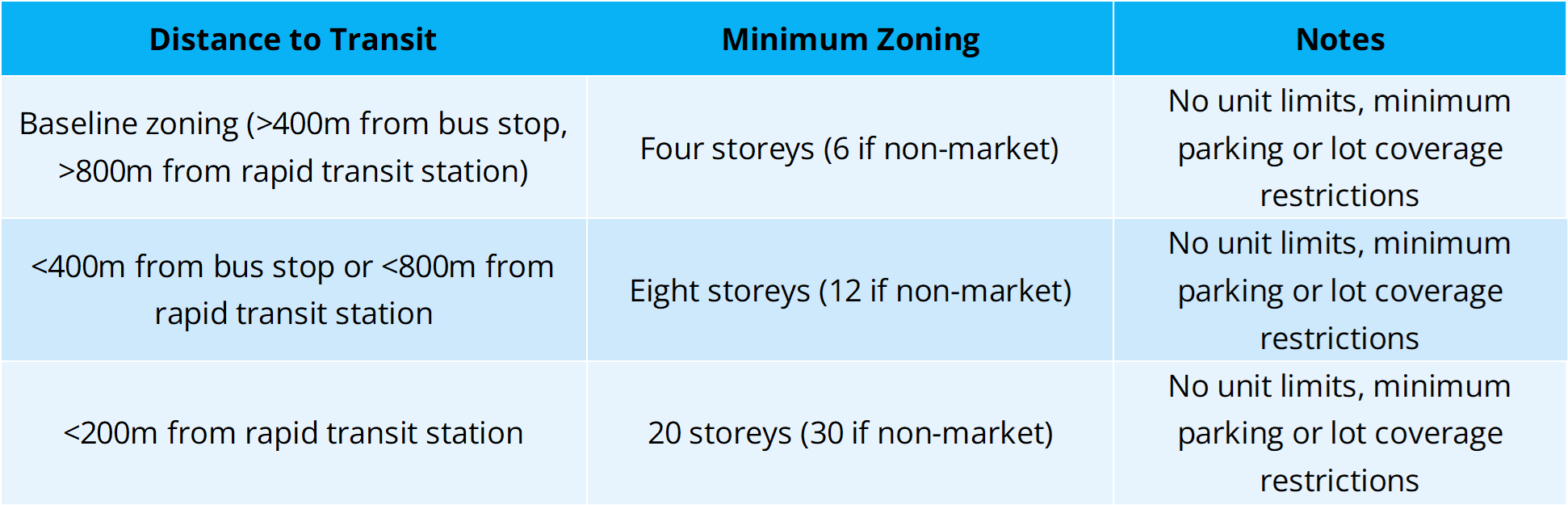

- Efficient zoning and approvals matter: An independent evaluation of Australia’s four year Social Housing Initiative (2009-2012) found that pre-zoning and delegated approvals on government land were a major factor in the $5.6 billion program which exceeded targets (19,700 new builds, 13% above target, as well as 80,000 renovations, including 12,000 homes that had been abandoned due to poor repair). Suggested minimum zoning below (Table 3).

Table 3. Suggested minimum pre-zoning for federal land

How to identify possible land parcels

Based on a Land Assessment methodology developed by the Housing Assessment Resource Tools (HART) project, there are three steps to an improved federal lands initiative:

-

Identification of all suitable federal land: The federal government can map all its suitable surplus, vacant and under-utilized ‘lazy’ land (e.g., parking lots where there are public transit alternatives). The starting point is its Directory of Federal Real Property. It should include all land, including Defence, surplus office buildings, etc. It should also include land held by Crown Corporations. For instance, there are over 3,000 properties directly owned by Canada Post: post offices, sorting, and distribution centres. There are more Canada Post Offices than Tim Horton’s, and over a larger geographic spread. Many of these buildings need upgrades for new environmental and economic functions, like electric charging stations for trucks. There is no reason why they can’t be redeveloped with affordable housing on top.

As part of suitability, parks, agriculture, floodplains etc. are excluded.

The federal government might also require, as a condition of transfers, provincial/territorial and municipal/regional governments provide similar open-source mapping of their land. They should certainly be requiring pre-zoning and as-of-right delegated approvals (no public consultation) as these have sped up delivery in the case of the Rapid Housing Initiative.

There is tremendous potential from non-profit land, particularly churches. The United and Anglican Churches are working with Kindred Works, the Salvation Army is considering an inventory of its land, and BC Housing Hub works with dozens of different non-profit organizations who donate land. - Prioritizing Well-Located Land: The CMHC has a proximity measures database that HART used to prioritize land near schools, shops, transit, etc.

- Supporting Larger Transit Sites and Sites Capable of Land Assembly: the federal government should prioritize larger sites of more than one hectare, especially sites near current or planned rapid transit.

- Requests for Proposals (RFPs) to lease this land for non-market and affordable housing: Based on National Housing Strategy targets as well as the NHSA, the federal government should be prioritizing its land to help subsidize deeply affordable non-market and supportive homes. It should also be modelling low GHG, fully accessible communities. Based on both the CMHC’s MLI Select mortgage insurance and the City of Vancouver’s Co-op Leasing Plan we suggest the following RFP criteria (500 points total).

Prioritizing the best projects

Any RFPs should prioritize the following categories and be scored accordingly.

Affordability and Adherence to NHS Targets (150 points)

- All proposed units must be affordable to median income households (0-120% of area median household income) (50 points)

- At least 40% is affordable to very low to low-income households (up to 50% of area median household income)[1] (50 points)

- Subject to Rapid Housing Initiative or other funding, at least 20% of the units are intended for supportive housing related to a Housing First approach to homelessness (low barrier, permanent) (50 points)

Priority populations (100 points)

- Proponent includes For Indigenous, By Indigenous partnership (50 points)

- Proponent addresses the need of another priority population e.g. women and children escaping violence, youth aging out of care, new migrant and asylum seekers, Black and other racialized community, people with physical, cognitive, mental disabilities and/or addictions, seniors (50 points)

Accessibility (50 points)

- In new build, 100% of units are universal design accessible in accordance with the CSA standard B651-18

- This criteria may be waived in the case of retrofit of existing buildings

- Partial points (up to 25) may be awarded for ground floor accessible units

Approval Readiness (50 points)

- Planning authority (municipality or region) has pre-approved zoning and has pledged delegated approvals in less than 90 days

Scaling Potential (50 points)

- Proponent has recent experience with large-scale development (at least 100 new or acquired units in past five years) (25 points)

- Proponent has recent experience with modular prefabricated housing (25 points)

Size Mix (50 points)

- In any new project that is not intended for supportive, seniors, or student housing, at least 25% of units be 2 bedrooms and a further 10% of units be 3 or more bedrooms

- This criteria may be waived in the case of retrofit of existing office or other buildings

Mixed Use (25 points)

- Ground floor mixed and active use is encouraged, particularly if the housing goes on top of social infrastructure such as schools, libraries, health centres, post offices, etc.

Energy Efficiency (25 points)

- In new build, a minimum of 40% better than NECB/NBC

- In retrofitted buildings, a minimum of 40% better than existing criteria

- Partial points (up to 15) may be awarded for 25% better than NECB/NBC or existing criteria

These guidelines can also be considered for provincial and municipally-owned land, of which there are thousands of hectares of vacant or “lazy” land owned by one level of government. By opening access to this land for affordable housing, governments in almost every community in Canada could make a real impact on our housing targets.

[1] This may require changes to current federal programs such as the National Housing Co-Investment Fund and Rental Construction Finance Initiative, as the only program that specifically funds low-income housing is the Rapid Housing Initiative.